C. difficile Patient Journey

C. difficile infection (CDI) occurs when Clostridioides difficile bacteria grow out of control in the digestive tract. The bacteria and their spores are resistant to many common cleaning methods so they can transfer easily between surfaces if people do not wash their hands adequately or follow strict cleaning protocols, which is why it is the most common form of infectious diarrhea in hospitals and long-term care facilities. CDI causes severe, watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, and fever. Left untreated, it can lead to dehydration that can be extremely dangerous and potentially deadly.

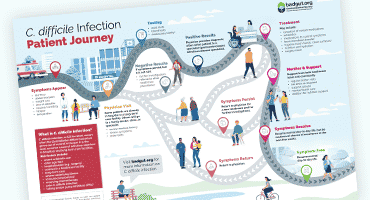

Each person’s journey has a different trajectory; from symptom onset to symptom resolution, it is often long, arduous, and filled with infection recurrences.

If you’ve been diagnosed with CDI, you might be feeling alone and anxious about your prognosis. Read on and view the accompanying diagram to learn more about some of the experiences of individuals with C. difficile infection.

CDI Patient Journey Video

How Does a Person Develop CDI?

There are two factors involved in C. difficile infection: gut microbiome balance and exposure to C. difficile bacteria.

Some people actually have C. difficile bacteria living in their gut, but don’t have any ill effect from it, as the bacteria balance is kept in check by other microorganisms. This is why taking an antibiotic can be a direct path to CDI. The antibiotic can kill off other bacteria, allowing any C. difficile present to grow out of control. Remember that many different healthcare providers (e.g., physicians, surgeons, dentists) can give you antibiotics, so make sure that if you develop new gut symptoms, you let your physician know whether you recently had antibiotics.

In other cases, a person can be exposed to C. difficile via contaminated foods or surfaces. Individuals who already have a compromised immune system are more likely to develop CDI after exposure, which is why people who are in hospital for a surgery, are older than 65 years of age, are receiving chemotherapy, are taking immunocompromising medications, or are living in a long-term care facility are more likely to develop CDI than younger individuals in good health. Sadly, those who have had an episode of CDI are at a much higher risk of developing it again.

CDI Patient Journey Infograph

Click here to view or download the PDF infograph showing the journey of a patient diagnosed with C. difficile infection.

How Does a Person Receive a CDI Diagnosis?

The main symptom of CDI is onset of diarrhea that is unusual for a person’s bowel behaviour. It typically involves at least six watery stools in 36 hours or at least three within 24 hours. In addition to diarrhea, the following symptoms can also occur: abdominal pain/tenderness, appetite loss, rapid weight loss, nausea, fatigue, dehydration, and sometimes fever. Many patients have underlying conditions that cause similar symptoms to CDI, such as inflammatory bowel disease, which make it difficult to diagnose CDI in a timely manner. If you have a bowel condition, it might take longer for you or your healthcare team to realize that the symptoms you are experiencing are different from bowel symptoms associated with your existing diagnosis.

However, there are some clues that help point healthcare professionals toward CDI, such as if you develop symptoms during or immediately after a course of antibiotics. If your physician suspects CDI, they will order a stool test to confirm the presence of C. difficile bacteria and/or its toxins. In some cases, they might also order a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, which are tests that allow the physician to examine inside your intestinal tract. The physician who diagnoses you with CDI will likely be either your family doctor or a physician on staff at a hospital, which can happen if you were hospitalized for another reason during symptom onset. After a CDI diagnosis, the physician might refer you to a specialist for treatment, such as a gastroenterologist or an infectious disease specialist.

What are the Typical Treatments?

Treatment can look different for each person and depends on how an individual developed CDI. In cases where antibiotic use likely played a role, it is often best to stop taking that medicine if possible. Some individuals are at an increased risk of developing CDI because they take proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to control gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), so temporarily stopping these medications might be necessary, but heed your physician’s advice and don’t change your routine without oversight.

While it might seem contrary, since antibiotics can cause CDI, different antibiotics are also the primary treatment for CDI. There are specific antibiotics that treat CDI best, including vancomycin, metronidazole, or fidaxomicin. The typical regimen involves taking an antibiotic for 10-14 days or, if there is a CDI recurrence, possibly for a longer time as part of a pulse/taper schedule. Never stop taking the antibiotics before the course is finished, even if you feel better.

Antibiotics tend to work quickly with symptom resolution occurring after a few days. However, it is important to take the antibiotics for the full amount of time, as instructed by a physician, so that it can fully eradicate the infection. While you might be nervous about taking an antibiotic if an antibiotic is what caused your CDI in the first place, it is important to remember several things: antibiotics are an effective treatment, CDI is not an allergic reaction to antibiotics, and even if antibiotics caused CDI for you before, they might not again.

Another therapy that can be helpful is fecal microbiota transfer (FMT). This involves taking material from a healthy person’s intestinal microbiota and transferring it to a sick individual, by enema or capsule, to improve the balance of the recipient’s microbiome. As it is a relatively new treatment, available in a limited number of centres in Canada, not every person with CDI will have this option.

Antibiotics (and sometimes FMT) are necessary to treat the underlying infection, but many patients require further help managing symptoms while they recover.

Eating while you are still dealing with C. difficile can be very difficult, but nutrient and fluid intake is important for recovery. Registered dietitians can play a valuable role in figuring out which foods and meal schedules will be best for your individual circumstances. Eating small portions of simple, easy-to-digest foods and taking sips of fluids throughout the day is important. Dehydration is extremely common in CDI, due to excessive watery stools. In those managing the infection at home, oral rehydration solutions (electrolyte beverages) can be helpful. However, those who are unable to manage oral fluid intake might require intravenous (IV) fluids in hospital.

Depending on your risk factors and symptoms, your physician might recommend other medications. In some extreme cases, such as an intestinal perforation, an individual might require surgery. Some people might use probiotics and/or prebiotics, with the goal to have these help improve the balance of the microbiome, but there isn’t much scientific evidence that these are helpful.

One very important part of treatment is stringent hygiene protocols. Avoiding sharing a washroom while you have diarrhea, and practicing thorough handwashing with soap and water and disinfection of surfaces with bleach diluted 1:10 in water can help prevent both the spread of C. difficile bacteria to others and the reintroduction of the bacteria to someone recovering from CDI.

What Comes Next?

As you recover from CDI, make sure to maintain good hygiene until you have finished the course of antibiotics. You are considered infectious until your diarrhea resolves. If your symptoms get worse or don’t improve after a few days, then go back to your doctor. While most people fully recover, the sad reality is that CDI recurrences are common. A recurrence is when you get sick again within eight weeks of the previous episode. The first time you get CDI, you have a 20-25% chance of recurrence, but after your second episode, the risk for a further recurrence increases to 30-45%, after the third episode this climbs to 50-65%, and you have more than a 60% chance of getting CDI again after a fourth episode. There is no way for your healthcare team to measure if it is gone for good or if it will recur, so make sure to let them know right away if you experience CDI symptoms again. It’s also a good idea to see your doctor for regular check-ins and follow-ups.

Some individuals who recover from CDI go on to develop irritable bowel syndrome or experience other gastrointestinal symptoms long-term. Speak to your physician about management options if this applies to you.

Managing Life With CDI

Depending on how severe your CDI is, it can have intense impacts on your quality of life. Some individuals need a caregiver, which can be a family member or a hired professional, to help support them through daily activities. It can also affect your ability to work, particularly if you experience many recurrences. Other individuals find the isolation required to prevent the spread of the disease to be particularly difficult.

On top of these issues, CDI is a highly stigmatized condition. Many people already view digestive symptoms negatively, and then add the fact that CDI is highly contagious, and many people feel ashamed and embarrassed. Patients who participated in a focus group with us in early 2022 expressed “feeling unclean” and “feeling like toxic waste”. There is a dire need for better understanding and education from the public and healthcare community of C. difficile infection so that more people are aware of the necessary prevention protocols and that patients get timely and accurate diagnoses. Privacy and dignity during treatment is vital.

There are community options to help you through your diagnosis, including financial programs and support groups. You might also find professional mental health support beneficial for working through the emotional impacts of CDI. Speaking with your friends and family, letting them know what it means for you to have CDI, and asking for help if you need it is also important. Educating others about the reality of CDI can help reduce stigma and make you feel supported and better able to cope with the condition.